The official version of this post is on the website of the Boston Musical Intelligencer and can be read here. Complete text follows. Enjoy!

-

In the expectant room a quiet composer, 18 musicians with 18 individual parts. The musicians count to 4 together, a silent “measure for nothing.” That’s the last gesture we’ll make together for most of the first movement of the new work we’re rehearsing for our concert at Jordan Hall on Friday

One by one, we Criers enter, playing quiet strings of harmonics and brief patterns of notes. We are eighteen birds, a group that is not yet a flock. Since we never play at exactly the same time, we follow a lovingly notated string of cues through the chaos of our tweets and flutters. We wonder together about how best to keep the invisible beat steady moving forward. At first, we assign the job of pulse-keeper to one individual, mirrored by others. But this is clumsy and creates a strange central point in the nearly aleatoric texture. Eventually we agree on a system where whoever is playing the cued line has the group’s attention – and in case of that person making a mistake, the next one can reset, and the next, and the next.

This whole scene, the whole conversation, the different techniques we try—it’s all somehow extremely relevant. We’re a democratic, self-conducted orchestra, and we’re getting ready to premiere a piece which is all about a group of birds learning how to govern themselves in the search for enlightenment. Lembit Beecher, the quiet composer, has known A Far Cry for a long time (and married one of our cellists, Karen Ouzounian, this past summer.) This piece he has written for us, titled The Conference Of The Birds, had its genesis nearly two years ago, and is coming to life now as a portrait, a meditation, and perhaps, a challenge.

In Lembit’s words:

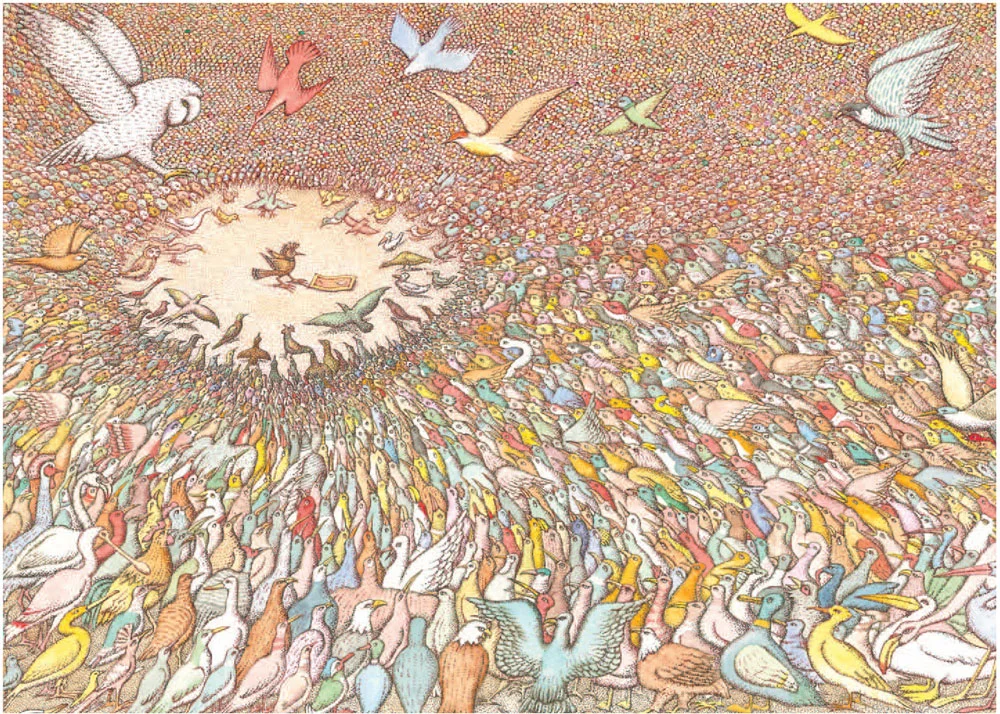

The Conference of the Birds” is a 12th-century Sufi epic poem by the Persian poet Farid ud-Din Attar. It tells a story about the birds of the world who gather together in a time of strife. Led by the hoopoe bird, they decide to set out on a long journey to find their king. Many birds desert or die along the journey, but after passing through valley after valley, the remaining 30 arrive at a lake at the top of a mountain. Looking in the lake at their own reflection, they finally see their king. I first came across it through an adaptation by the brilliant Czech-American illustrator and author Peter Sís. … What drew me to Sís’s version, aside from the expressive, textural drawings which so suggested music, was the deep sense of loss in the pages. So many birds are left by the wayside during this journey towards truth and enlightenment. Does progress or attempted progress always come at a cost?

When I began talking to A Far Cry about writing a piece, I realized this would be a perfect project for the group. Having gotten to know the group, I wanted to write music for individual personalities: each member of the ensemble has his/her own part. These parts join each other in different combinations, but just as quickly split up again. The leadership of the music, and the relationship of individuals to the group is always changing. As I wrote I thought about the power of crowds, and the value of individuality versus unity, but I also thought about the players of A Far Cry, and how much I admire the way they function as an ensemble, share leadership, and make music together.

As we reach the end of the first movement, the musical lines begin to “infect” and inform each other. The birds begin to converse with each other, and as they do, a collective pulse emerges out of the texture. As this grows in intensity and shared purpose, the birds’ intention unifies into a single powerful flapping of wings. Slowly accelerating, they reach a lift-off point and start flowing up together into the sky. The violins of A Far Cry soar higher and higher on their instruments until we can barely hear them – and barely see the flock, now impossibly far away, which has now embarked on its perilous journey.

This is only the beginning for the birds, but it gives us plenty of food for thought. How do you move from a state of stasis to a state of movement? How do you move from a collection of like-minded individuals to a group unified enough to actually be capable of powering its own flight? We’ve spent years wrestling with – and living out – these questions.

Now here we are, playing a program, anchored by Lembit’s new piece, that addresses some of these issues head on. In the rest of the concert, we present two unconventional double concertos—Bach’s Concerto for Two Violins and Arvo Part’s Tabula Rasa – and some haunting “pilgrim” music; selections from the 12th-century Codex Calixtinus. The concertos, played by Stefan Jackiw and Alexi Kenney, are as much vehicles for collaboration as they are for virtuosity, and circumvent the traditional ideal of central leadership.

As Karen Ouzounian, one of the program’s co-curators, puts it:

We wanted to explore the idea of leaders, false prophets, the search for enlightenment. We have these incredible soloists coming to join us, but the pieces they’re playing aren’t exactly flashy solo concerti. Instead they have a beautiful relationship to the group where the continuo is just as important as the solo voices.

Alex Fortes, the other co-curator, goes even further:

There’s an expression which people often use who have no idea what the original context is; playing second fiddle. It has a pejorative feel to it. And one thing about this concert is that everyone onstage, including each of our soloists, is playing second fiddle at some point in the program. In a way, that’s what it’s about. Sometimes we strive for this ideal, for a strong hierarchy, some leader that will make everything better, or some smooth process. And it never works out that way. Even when things work out beautifully – there’s tension that’s always underlying our best work.

How do you move forward in a situation where all the traditional norms are called into question? Where the traditional values of unchanging, centralized leadership are not necessarily in play? (It’s perhaps worth mentioning here that A Far Cry is absolutely not anti-leader; if anything, the group is full of leaders.) One interesting first step is to “unlearn” some of what you thought you knew, and as such, it was a great pleasure to hear our soloist Stefan Jackiw say this about the Bach Double:

Fortunately, I didn’t play it when I was young! Even though I didn’t study it as a kid, though, I still felt like I had to unlearn all these years of interpretations and varnish lacquered on to the piece, and really strip it away and go back to what Bach wrote.

That ability to “unlearn” has been on beautiful display from both Stefan and Alexi all week long, as they’ve worked within the framework offered by A Far Cry, making suggestions directly to the group at large, and participating in group discussions on phrasing, tone color, pulse, character – moderated in part by the principal groups for the individual pieces.

Of course, everyone has also learned plenty in this process. After all, it only works if it works, and it works if you can share information accurately and well with each other. No matter what system you use—democratic or dictatorial —the frame needs quality content within it; interesting ideas, virtuosic execution, a commitment to moving the music forward into the best version of itself that we can render.

To return to Lembit’s piece; the end of the work demands a totally different set of musical tools than the beginning. In the opening, we had to represent a distracted, scattered, group; at the end, what remains of the flock is stunningly unified and radiant. For the musicians, that means developing a technique of playing this last section that really sounds entirely like one ecstatic voice. It couldn’t be a more different style than the one we were embodying when the work began.

A complicated work that keeps evolving and presenting us with new issues to address (and allowing us the chance to grow in the process?) Yes please! We wouldn’t have it any other way. If there’s one thing A Far Cry has learned in its first ten years, it is that challenges, even complicated ones, are usually opportunities.

- Sarah Darling